We had to capture a small number of grayling or dolly varden this year to begin experiments on their feeding behavior and learn how to adjust the lab environment for their capabilities. By the time we were ready to receive fish (October 1st), winter was already creeping in on our study stream in the foothills of the Alaska Range.

My job was to bushwhack up the creek with a bucket of water and a bunch of other supplies to catch fish and keep them safe for transport. I tried using my fly rod and some collapsible minnow traps, and I also brought a GoPro on a telescoping pole with an HDMI live viewer to scope out the locations of fish I might not find otherwise.

It was generally more difficult to find fish at this time of year than during the summer. Grayling were nowhere to be seen, but I found a few dolly varden in the biggest pools. The minnow traps were completely ineffective, even when placed in a pool right next to dollies I found on camera. But my fly fishing skills did not fail me.

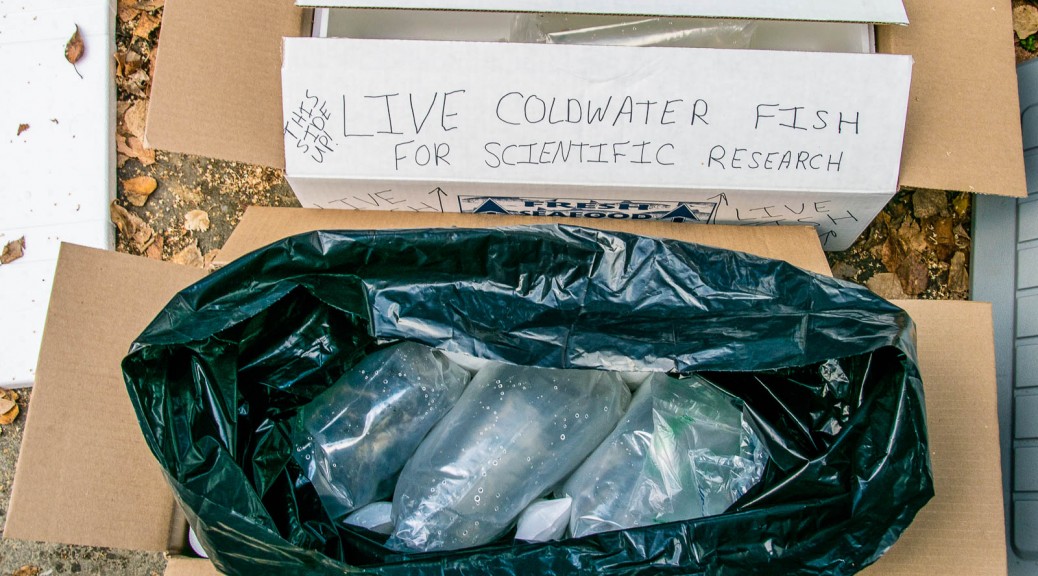

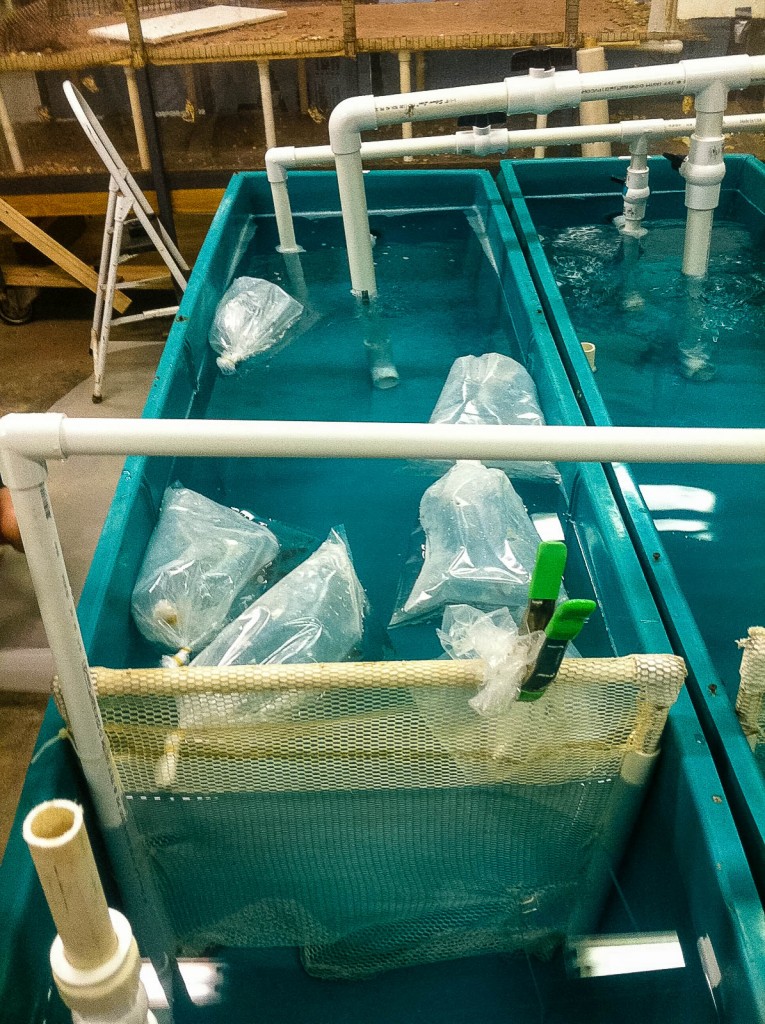

Like the Chinook salmon, the dollies we collected survived the trip to Georgia in great shape. However, I was asked to send a few more a couple weeks later. Unfortunately, conditions on the creek were not very conducive to catching fish.

Not wanting to completely give up after the long drive, my friend Trevor (a labmate at UAF who also finished his Ph.D. this summer) and I hiked three miles up the icy river bed searching for fish. We stuck the GoPro through gaps in the ice to investigate all sorts of likely habitat, but there were almost no fish to be found — just a few that spooked out of the shallowed riffles and were long gone before we could try to catch them.

The only fish we could have collected was a slimy sculpin we found, frozen solid and perfectly preserved, out in the open on top of the ice. We left it to rest in peace.